Brace for impact! Kawasaki has crashed the party again, this time with a 300-horsepower supercharged motorcycle for closed-course operation only. No muffling, no emissions, no DOT.

Again? In 1972, in the middle of a sleeping market much like today’s, Kawasaki released its super powerful H2 two-stroke triple, which was absolutely the most bang for the buck available. Nothing could stand against it. The racing H2R version of that triple now gives its name to the 300-horse Kawasaki unveiled today at INTERMOT 2014, the motorcycle show in Cologne, Germany.

The motorcycle market has been steadily moving upscale for years, with manufacturers aiming products at those with disposable income. The farther this process goes, the more radical and exotic must be the offering to give those buyers a reason to act. The old mass market and commodity motorcycles are losing traction. Kawasaki knows that strong identity is central to success in future. Here it is.

Not just a Straight Line Machine:

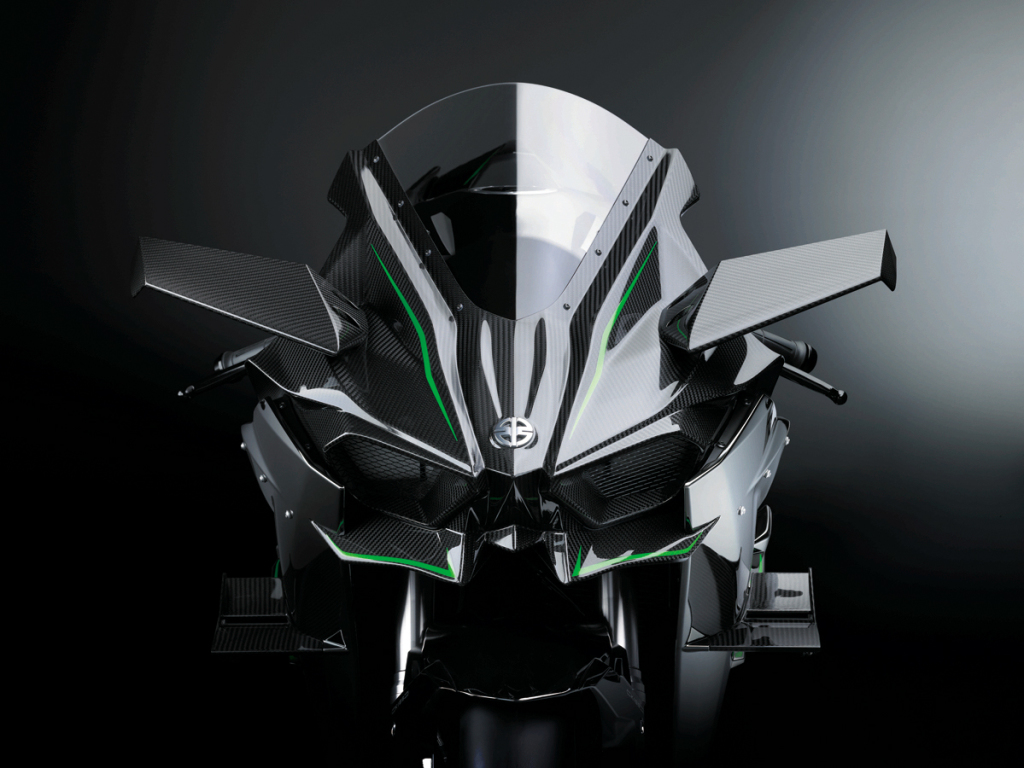

Kawasaki’s press release makes it clear that the new Ninja H2R is not another slow steering, power-laden straight-liner. Moreover, its engine is a “a compact design similar to power units found in the supersport category.” And the only way to pack big power into a small package is to supercharge—to stuff into a modest-size engine all of the fuel-air mixture of a much larger engine. The chassis has trellis construction, and the bodywork, which must be right for high-speed stability, comes from the wind tunnel.

Supercharging—compressing air before delivering it to the engine intakes—raises the temperature of that air. When Kawasaki supercharged the 1500cc ZX-14-based engine of its Ultra 300X watercraft, the company used a blower similar to those seen atop every Top Fuel drag car. Such Roots blowers are effective across an engine’s rpm range but they generate a lot of heat. Pushing hot air into an engine pushes its combustion toward detonation, the destructive abnormal combustion that blasts metal off of cylinder heads and pistons. That was no problem on the watercraft, which have unlimited cold water available for operation of a charge air cooler, or “intercooler” (people like the term, but it’s actually a misnomer. On wartime aircraft piston engines, multi-stage supercharging systems were common, and a cooler placed between stages was therefore called an intercooler. When there is only one stage of supercharging, engineers prefer to call it a “charge air cooler”).

Where would you put an intercooler on a bike? And how would you duct a high volume of cooling air into and out of it?

Kawasaki therefore chose the most efficient of all blower types, a centrifugal supercharger. The more efficient the blower, the less it heats the air it compresses (isn’t that almost always where wasted energy goes, into heat?). In a centrifugal blower, a rotating disc carrying tapered radial vanes on one or both of its faces rotates at high speed. Air entering along the axis is flung outward by the vanes and is accelerated to very high speed, typically somewhat more than the speed of sound, which is 1087 feet/second at sea level). Air flung from the vanes enters a surrounding scroll-shaped passage in which velocity energy becomes pressure energy. The special capabilities of Kawasaki Heavy Industries’ Gas Turbine and Machinery Co. were called upon in the design of this supercharger. Yes, Kawasaki produces both jet engines and electricity-generating turbines.

Engine:

A Kawasaki ZX-10R superbike engine of 998cc displacement takes in roughly 7,000 liters of air per minute. But if a compressor forces twice that volume of air into it, its horsepower will double. A limit is set to this process by heat. As the combustion flame spreads from the spark plug, expansion of hot combustion gas compresses the unburned charge remaining. As unburned charge is heated by this compression, pre-flame chemical reactions within it accelerate. If these reactions go far enough, bits of unburned charge go off before the flame front reaches them, generating shock waves of sonic-speed combustion that make the noise we call “combustion knock,” or detonation. The destructive effects of detonation set limits to our power hunger. Typically, compression ratios of supercharged engines are lower than those of unsupercharged engines to subject the fresh charge to less heating, thereby staving off detonation. Supercharged aircraft engines of WW II typically had compression ratios around 7:1, while engines of F1’s first turbo era ran at about 9.5:1. Splitting the difference, we get about 8.25:1.

Won’t this lowered compression reduce engine torque? You bet, but maybe around-town performance is unimportant for a track-only bike. Or this may further support the idea that Kawasaki has torque-flattening technologies we have yet to see.

Many of us have seen the Kawasaki patent drawings and text available on the Internet. They show the supercharger drive packaged into the space behind the cylinder block of a transverse in-line engine. Gear teeth cut into one of the engine’s flywheels turn a jackshaft behind the cylinder block. That shaft in turn drives a shaft above it, ending in a compact planetary step-up drive just before the centrifugal impeller itself. The impeller is small, as the very similar-in-concept impeller from one of my R-4360 aircraft engines has a diameter of only 14 inches (4360 cubic inches, by the way, is 71 times the displacement of a ZX-10R). Compressed air output from the blower’s scroll housing flows upward, pressurizing the intake airbox above it (which is presumably something more robust than the usual Samsonite-looking ABS structure). In Cosworth fashion, we can expect normal-looking throttle bodies and bellmouth intakes, projecting up into the box from the engine’s cylinder head. Cosworth engineer Keith Duckworth once said that a supercharged engine is just a normal engine operating at the bottom of a really deep mine (where air pressure is higher).

Specifications:

| ENGINE | Supercharged inline-four, liquid-cooled |

| DISPLACEMENT | 998cc |

| SUPERCHARGER | Centrifugal, scroll-type |

| MAXIMUM POWER | approximately 300 hp |

| FRAME | Trellis, high-tensile steel |

| FRONT TIRE | 120/600R-17 (racing slick) |

| REAR TIRE | 190/650R-17 (racing slick) |

The Blower:

Although patents are written as broadly as possible, what we can see on the web shows a dog-shifted two-speed drive to the supercharger shaft. Why? This might be because the output of a centrifugal blower increases as the square of rpm. Thus, if the blower was delivering a modest 5 psi of boost (that’s 5 psi above atmospheric) at 6,000 rpm, it would be trying to deliver 20 psi boost at 12,000.

Why not just go with that? One problem: The resulting torque curve would rise so steeply that it would make the bike unrideable. One way to change that is to run the supercharger on a high ratio at lower engine rpm, and then at some point shift to a lower ratio to limit top-end torque to something usable. Best of all would be a continuously variable supercharger drive that could keep boost constant for improved rideability.

Control:

Aside from providing “the kind of acceleration no rider has experienced before,” Kawasaki also wanted a chassis and aerodynamics that would deliver “unflappable stability,” “cornering performance,” and what the company calls “an accommodating character.” The H2R is to be an all-around motorbike, and for that reason it can be expected to carry civilizing electronics, including KTRC traction control, KEBC engine braking control, and KLCM launch control. That stated, racing slicks on the 17-in. wheels remind us that this a track bike.

Extensive aero work was done at Kawasaki’s Gifu wind-tunnel facility (back when we were racing the original H2Rs, our technician, Kazuhito Yoshida, told us “At Gifu, many smart guys.”). The result? “Wind tunnel-sculpted bodywork” that’s very different from the design-college exercises currently thought of as “streamlined.” I’m glad, because I am heartily tired of the conformism of sharp edges, points, and scoops so studiously cribbed from corroding 1950s jet fighters.

How Fast?

How fast will 300 horsepower drive a motorcycle? Back in 1973, our H2Rs made about 90 hp and reached just over 170 mph. As speed increases roughly as the cube root of the horsepower ratio (which is 300/90 = 3.33), that suggests 1.5 x 170 = 250 to 260 mph. But come back to earth: If we geared the H2R for that dreamland top speed, we’d be shifting out of first at 110 mph!

The chassis chosen for this creation is a steel-tube trellis design. In the words of Kawasaki: “The frame needed to be stiff, yet had to absorb external forces encountered while riding in the ultra-high speed range.” All motorcycle manufacturers now study and quantify the stiffness of their chassis in various planes, so when they state that “a new trellis frame was developed using the latest analysis technology,” they are talking about something real. As compared with a classic twin-aluminum-beam Cobas-type chassis, a trellis presents much less obstruction to airflow over and around the engine, which can be responsible for up to 10 percent of the cooling.

Next is What?

If, in 1972, if we had reasoned backward from H2R to H2, we’d have proposed there must be a street-legal H2 production bike. So there was. We don’t have to look for perturbations in the orbit of Neptune to suggest the existence of “something else out there” when we consider this new Ninja H2R. So we wait and see.

The present motorcycle market desperately needs this poke in the eye. Wake up and take notice! Get cracking! When we look at the current crop of 1000s, all date from before our present “recession,” and what little has come by way of new product has sought to please the mostly imaginary “new buyer” with low-tech delights. This makes me recall long-ago auto writer Tom McCahill, who once referred to US auto engines of his era as “dehydrated panda sixes and squirrel hormone eights.”

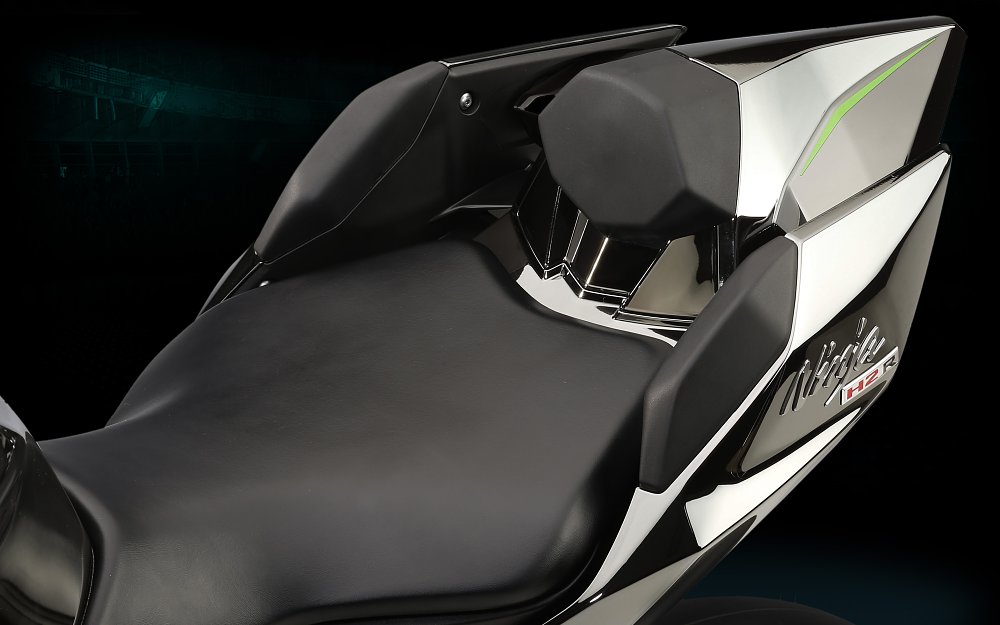

Kawasaki is proud of this creation, and is allowing the H2R to bear the River Mark logo, a symbol from the KHI Group that dates back to the 1870s. Its use, we are told, is “limited to models with historical significance.”

Video: